Mathematics low-tech & high-tech: using manipulatives to further understanding

Maths

“In mathematics education, a manipulative is an object which is designed so that a learner can perceive some mathematical concept by manipulating it, hence its name. The use of manipulatives provides a way for children to learn concepts through developmentally appropriate hands-on experience”.

(Wikipedia)

Every high school teacher knows the challenges her or his learners face when trying to transition from the concrete concept of numbers to the abstraction that is algebra. Too often we downplay this or are defeated by it, coming to the erroneous conclusion that some kids simply cannot do mathematics. Teachers and parents often perpetuate this view, treating Mathematics as an imposed set of rules which have been forced on us and which only a privileged few can access and make sense of.

The reality is that all of Mathematics is a human endeavour and all of it was created by people to help them make sense of our world. Highly effective teachers are relentless in assisting their learners to come to understand this. They do so by looking for every opportunity to connect maths to the world in which we live and to help those in their care make the connections between different aspects of the subject. “Konke kuhlangane nakonke ezibalweni” – everything is connected to everything else in Mathematics.

One effective, but often overlooked, way of “making it real” and building bridges between concrete concepts and abstract ones is through the use of manipulatives. Manipulatives give young people the chance to touch, feel and engage with maths in order to make it more accessible, less stuffy, and not so highfalutin. While by far the best way to understand the power of manipulatives is to watch learners engaging with them, I will try my best to unpack some examples in this article.

Consider the teaching of the concepts of perimeter, surface area and volume. The traditional and, sadly, most common point of departure is to present students with a bunch of formulae with little regard for their provenance. These are followed by an instruction to embark on pages of examples from an oftentimes dull textbook. An alternative and, in my opinion, a far more compelling approach would be to give each student a handful of 1cm3 blocks. edx Education sells these in a jar of 1000 for around R400.

Here are some questions which one could pose to a junior high school class – although not all in the same lesson!

- Using 24 cubes see how many different rectangles you can make with a height of just one cube. What is the perimeter of each? What is the surface area of the top of each?

- Using 24 cubes see how many different rectangular prisms you can make. What is the total surface area of each? What is the total volume of each? Which has the smallest surface area? If one could cut cubes up, could one make an even smaller surface area with a volume of 24 cubes (24 cm3)?

- Make two rectangles which are similar. What is the ratio of their sides? What is the ratio of their areas? Is there a relationship between these ratios and, if so, why?

- Now make two rectangular prisms which are similar. What is the ratio of their sides? What is the ratio of their volumes? Is there a relationship between these ratios and, if so, why?

- Using only 2 colours see how many different patterns you can make using 3 cubes. For example, if B represents blue and Y yellow then we could have BBY or BYB or YYB or ….

- If we put the same number of blue, yellow, green, and red cubes in a bag then what is the chance of randomly drawing out a cube which is not green?

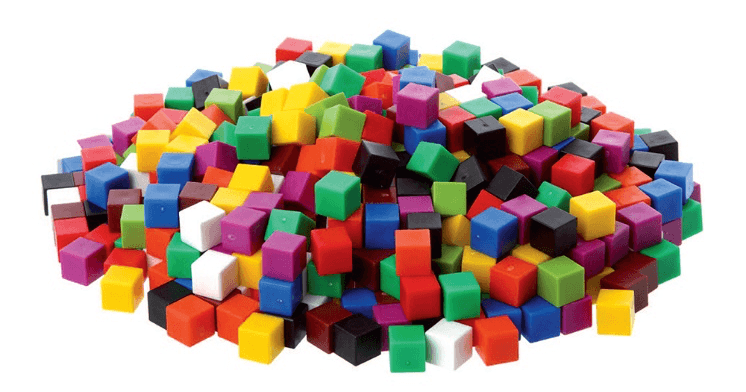

- Make the following sequence of patterns out of blocks

How many blocks will you need for fig. 5? What about fig. n? Which figure could you make with 65 blocks?

By engaging with all of the above there is no doubt that learners would have a far more intuitive feel for the concepts of area, total surface area and volume. They will also have discovered that it is more efficient to calculate areas and volumes by multiplying dimensions than by counting blocks. They will have essentially discovered the formulas for area and volume all for themselves. This knowledge is far more likely to be internalised than if they had read it in a book.

Learners will also have reinforced the commutative law of multiplication, and a better understanding that 2 x 4 = 4 x 2. They will know that a 4 x 2 rectangle and a 2 x 4 rectangle are the same rectangle (congruent), just positioned differently (rotated). Number patterns and probability will have become real and therefore more meaningful.

Above all, they will have had fun and they will have been engaged with mathematics. Engagement is, after all, the lifeblood of learning. Don’t get me wrong. I am not suggesting that we simply dish out some blocks and let them play in a completely unstructured manner. I would suggest a supporting worksheet which poses challenges, giving them space to record their results and their findings which, by the way, are different things entirely.

A second example would be the discovery, through engagement with manipulatives, of some of the key results in Euclidean Geometry. Start by getting every student to draw his / her own triangle, cut it out and tear off the corners. They should ALL be able to arrange their angles in a straight line – a demonstration (not a proof) of the fact that the interior angles of a triangle always add to 180o.

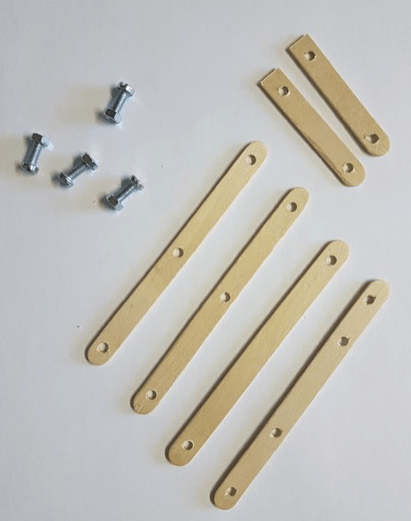

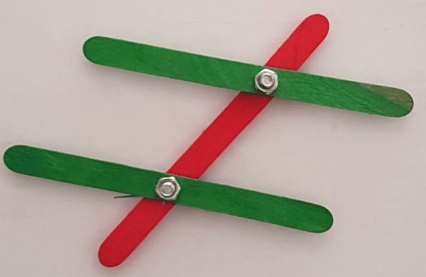

The set of sucker sticks shown alongside allows students to engage with the various angles formed when a transversal intersects a pair of lines. By moving the sticks and observing the angles they will come to their own realization that alternate and corresponding angles are equal but only when the lines are parallel.

The students can also build a dynamic parallelogram and use it to discover the properties of a parallelogram all for themselves. Through this process, they will come to fully understand why all rectangles are parallelograms but not the other way around. They will also come to appreciate why a rectangle, as a special case of a parallelogram, has some additional properties. The kit also allows them to construct a dynamic rhombus as well as different types of triangles, all of which are rigid. To the best of my knowledge, such a set of sticks is not available commercially at this time. I hope this might soon change. Until then, it is a simple matter to buy these sucker sticks in bulk and drill some holes in them.

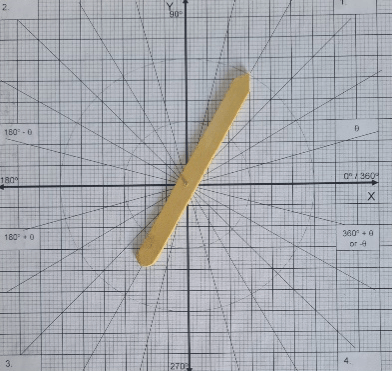

When I was at school, each of us made a trig. a board like the one pictured alongside. By engaging with this simple piece of “technology”, taking readings, calculating ratios, and drawing trig. graphs we came to a far deeper understanding of trig. functions and their periodic nature than we could have through any other means. This, in turn, helped us really understand what we were doing when doing trig. reductions, solving trig. equations etc. I do not believe that there is a better way of introducing young people to trigonometry and, as such, it is the way I have done so ever since I started teaching.

Digital manipulatives are readily and freely available online (visit www.shayaizibalo.com) and they too allow for deeper engagement and the establishment of a feel for what is going on. Consider this example which allows us to engage with all the different variations (5 of them) of the angle at centre theorem, helping us understand that the angle in a semi-circle is just a special case.

I hope that the above examples will whet your appetite to make greater use of manipulatives in your teaching. Your students will be eternally grateful. I hope too that you will not hesitate to contact me ([email protected]) if you feel I can help you on this exciting journey.

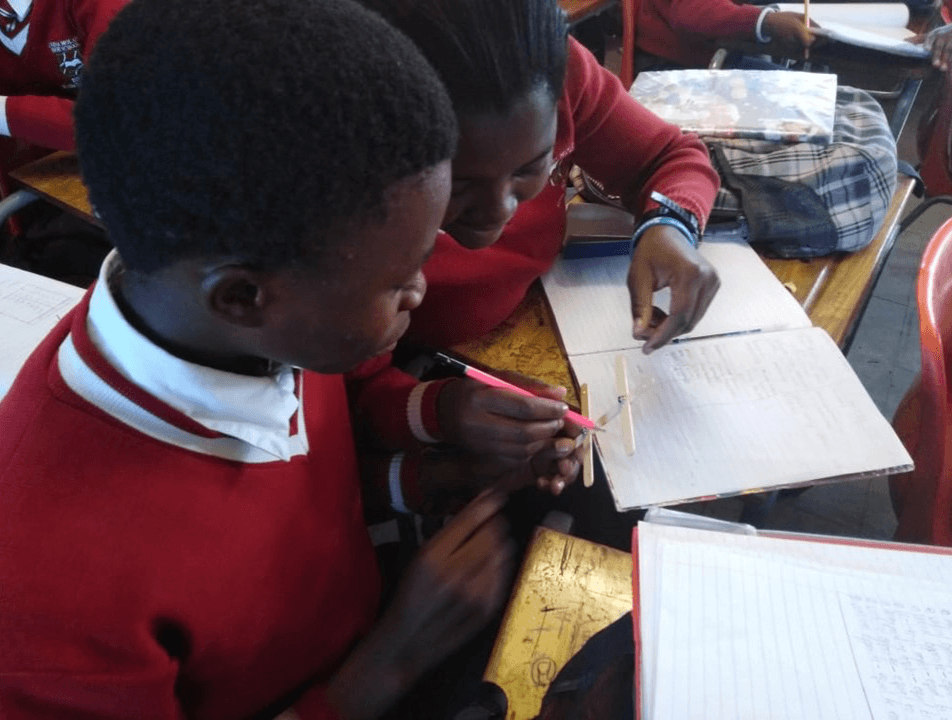

Learners at Kwena Molapo Secondary School engage mathematics with a manipulative

This article was originally published on 28 Nov 2022

About the author

Paul de Wet

Paul is a leading mind in Maths Education at a High School level in South Africa having led and directed Maths and Academics at both Hilton and Michaelhouse. He is currently the IEB Further Studies Maths (previously AP Maths) Examiner and the Director of The Shaya Izibalo Maths Institute that works to provide Mathematics resources and services to secondary schools, particularly in less privileged spaces. His first passion is teaching Mathematics and his underlying motivation is to use his abilities, experience, and energy to give back and make a difference to those who need it most.

Unlocking Opportunities with Further Studies English: Faye’s Journey of Growth and Success

Uncategorized

Our recent Further Studies (AP) English webinar gave a firsthand look into the significant advantages of Further Studies programmes. With the inspiri... Read more

Why Take Further Studies Subjects: Your Pathway to Academic Success

Uncategorized

Are you a high school student in Grades 9, 10, or 11, and looking to stand out in your academic journey? If so, then Further Studies programmes might... Read more

How Further Studies (AP) Maths Helps At University

Further Studies

FS Maths

Featured

At Advantage Learn, we are dedicated to empowering learners with the tools they need to succeed in higher education and beyond. Our recent Further St... Read more

Do you want better Maths results?

Maths Online is a bank of over 2000+ extra lessons. Furthermore, gain access to our teacher support to help you when you need it!

More info